This is the 293rd edition of SHuSH, the newsletter of The Sutherland House Inc. If you’re new here, press the button:

Sutherland House is always happy to receive submissions of manuscripts or proposals for nonfiction books. If you are looking to get published, contact submissions@sutherlandhousebooks.com. Agents welcome, but no agent required.

This is chapter four of our look at Bloomsbury Publishing, the most successful new book publishing venture in the last half century. I’ve left part one, SHuSH 286, “The Bloomsbury Miracle,” part two, SHuSH 287, “An Exceedingly Fortuitous Moment,” and part three, SHuSH 290, “Bloomsbury before it got lucky,” outside the paywall for those of you who aren’t caught up.

We last saw the four original partners of Bloomsbury ten years into their adventure. Things were going so-so. They had exchanged equity in the company for large amounts of capital so they could compete with the big publishing houses even as a start-up, a decision that left each of the original partners with surprisingly small stakes in their own creation. They were producing good books, winning prizes, and growing revenues, but earnings were insufficient from an investor perspective: their share price was in the toilet despite a boom in public markets. That left Bloomsbury a failed investment vehicle, with its outside shareholders controlling its fate. CEO Nigel Newton needed a break.

The Harry Potter origin story will be quite familiar to those who follow the franchise. First-time author J. K. Rowling’s manuscript had been rejected by a dozen or so publishing houses. Her agent, Christopher Little, finally took it to Bloomsbury, which had recently launched a children’s line. CEO Nigel Newton gave a chapter to his daughter, Alice. “She came down from her room an hour later glowing,” says Newton, “saying ‘Dad, this is so much better than anything else.’ She nagged and nagged me in the following months, wanting to see what came next.”

According to The Independent, Newton knew “he had a winner on his hands.”

It’s a nice story, not entirely accurate. From what I can tell, and no disrespect to little Alice, it was Barry Cunningham, founder and publisher of Bloomsbury Children’s Books, who saw something in Rowling. He’d received her manuscript, circulated the first three chapters of her manuscript to staff, and asked them to read it.

Cunningham says his earlier experience working with Roald Dahl at Puffin (a division of Penguin) helped him spot Potter’s potential. "I think it was because I didn't come from a traditional background. I'd come from marketing and promotion. I'd seen how children relate to books, so I perhaps wasn't looking for those kinds of books that tried to teach them lessons, or tried to be good for them." He read the Potter overnight, “and I suppose the beginning did slightly remind me of Roald Dahl—Harry and his cupboard. But the other thing was the bond between the children and the friendship and very, very importantly—and, again, unusual for any kind of fantasy at that time—was the humour.

While he liked it, he wasn’t over the moon. “I wouldn't pretend to you I predicted at that time though that Harry would take over the world, and then have all those adult readers, [that] it would be so important to multi generations. I didn't predict that."

Rowling, not incidentally, credits her discovery to Cunningham. Without him, she says, Harry Potter "might still be languishing in his cupboard under the stairs." Three years after these events, Cunningham left Bloomsbury to start another children’s publishing house, which may help to explain why his role is downplayed in the origin story.

Another problem with the story is that Bloomsbury gave J. K. Rowling, a single mother who was having trouble meeting her rent, a humble advance of £2,500. The first print run was just 500 copies, 300 of which were destined for libraries. That’s not how you treat “a winner.” Little Sutherland House has never had a press run that low—500 copies is risk mitigation.

Nobody at Bloomsbury or anywhere else in the industry was expressing high hopes for Rowling’s book in the months leading to its release in 1997. Agent Little was probably relieved to have cleared the manuscript off his desk—he’d already put in a lot of work for a commission of a few hundred pounds.

Anyway, things worked out. One of those original 500 copies of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, a former library book that was circulated twenty-seven times, recently sold at auction for $88,140 US. Others have gone for $120,000.

The author herself is beyond the scope of our series—our focus is Bloomsbury—but I do want to pass on the most interesting thing I’ve read about J. K. Rowling. It was in the diaries of actor Alan Rickman, who played Harry’s teacher, Severus Snape, in the Potter franchise’s movies. He called her up, wanting some insight into his character. “Talking to her,” he said, “is talking to someone who lives these stories, not invents them. She’s a channel—bubbling over with ‘Well, when he was young, you see, this that and the other happened’—never ‘I wanted so & so…’”

Everything happened at once for Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone. A news report two weeks before its release announced that the Scottish Arts Council had given Joanne Rowling, as she was still known, its largest ever grant of £8,000—more than triple her advance; the council called her book “a terrific read and a stunning first novel.” One week before its release, Scholastic bought the US rights to Philosopher’s Stone for just over $100,000 in an auction involving ten publishers. A week after its release, Hollywood studios were competing for the film rights. Eventually, David Heyman’s Heyday Films, part of Warner Brothers, paid seven figures for the rights to the first two Potters.

The book was published in the US as Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, because American readers were presumed by American publishers to be too dumb to deal with “philosopher’s stone.” It topped the New York Times bestselling fiction list in the summer of 1999, a year after its release, and stayed there until late in 2000.

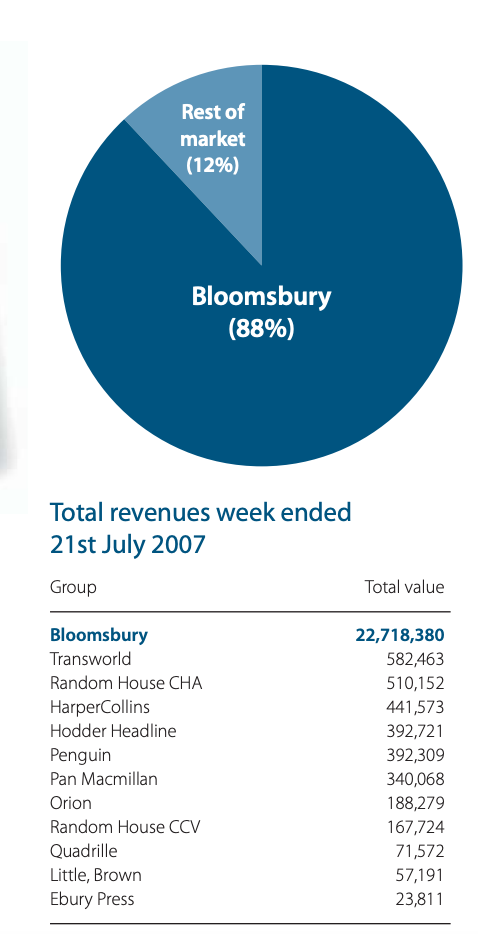

Six more hardcovers rounded out the Harry Potter series, at the pace of one a year from 1998 to 2000, then one every two years between 2003 and 2007. They contained a total of 1,100,086 words. Here’s what happened in the UK the week of the release of the last book in the series, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows:

There followed paperback editions of each book, illustrated editions, new jacket editions, a boxed set, three companion books.

The sales stats are mind-blowing. Philosopher’s Stone alone has sold 120 million copies, which makes it one of the best-selling books of all time. There’s no way of saying exactly where it stands, because there are no accurate sales data for The Bible, Don Quixote, A Tale of Two Cities, and most other books published before the Second World War. It would appear to be the bestselling book published in English in the last century. Globally, it trails only Paulo Coelho’s The Alchemist (150 million) and Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince (200 million). It seems only a matter of time until it passes them.

By the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Potter series in 2022, 500 million copies had been sold. We’re now over 600 million. It is said to be the best-selling series of all time.

Here’s a selection of data points that together give a sense of what Harry hath wrought.

Total revenue for the Harry Potter books is estimated at $7.7 billion.

The initial US print run for Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows was 12 million copies. It sold 8.3 million in the US within twenty-four hours of its release. Another 2.7 million were sold in the UK.

The last five books in the series sold worst, if 65 million copies can be considered worst.

Thirty-one per cent of Americans report having read at least one of the Potter books.

Rowling maintained rights to her digital and audio editions. She released Harry Potter e-books on her own website in 2012. Sales amounted to $95 million in 2016 alone.

Four billion minutes of Harry Potter audiobook listening occurred between 2016 and 2018. As of November 2022, the series has accounted for a billion hours of Audible listening.

The eight Harry Potter movies have grossed about $9 billion. Seven of them are among Warner’s twenty-five best-performing films of all time.

The Hogwarts Legacy video game generated $1 billion in revenue three months into its 2023 release.

Harry Potter theme parks exist in Orlando, Osaka, Hollywood, and Beijing. Operator Universal Theme Parks had gross revenues of $37 billion between 2010 and 2020; it is estimated that the Potter parks accounted for a third of that.

The entire Harry Potter franchise, with books, films, video games, theatre plays, theme parks, Lego sets and other merchandise, was estimated to be worth in excess of $25 billion in 2016.

HBO’s original Harry Potter television series began production in the UK last week and is set to debut in 2027. It will involve so many child actors that a school has been built with a capacity of 600 pupils; it is expected to operate for the next eight to ten years. Roughly 32,000 children were auditioned for the lead roles.

That covers Bloomsbury Publishing’s acquisition of Harry Potter, and what Harry Potter has done in the world. Obviously, Harry Potter was the best thing that could have happened to Bloomsbury, but as we’ll see next chapter, success came with some enormous headaches.

New from Sutherland Quarterly

Sutherland Quarterly is also pleased to announce its newest edition, The 51st State Votes, by one of Canada’s most talented young journalists, Justin Ling. Here’s what it’s about:

In April, 2025, twenty-million Canadians cast ballots in an election defined by economic turmoil, a cost-of-living crisis, and threats of outright annexation by the United States. It was an election that, more than any vote in recent memory, split Canadians down the middle.

On one side were voters convinced that their own country had been broken by years of abuse and mismanagement—Canadians who no longer believed in the state's ability to do its job, let alone build big things, and never mind fight and win a trade war. On the other side were those motivated by the existential threat posed by a single man: Donald Trump.

Over thirty-five days of campaigning, Liberal leader Mark Carney and Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre criss-crossed the country speaking to those duelling anxieties. Journalist Justin Ling watched it all from up close, paying particular attention to how Canada’s 45th general election scrambled its priorities and put the country at the forefront of the global resistance to a mad American president.

Smart, witty, and superbly observed, The 51st State Votes is a gripping account of a campaign that promises to define Canada for the next century.

As a SHuSH reader, you are eligible for this special offer: buy a subscription to Sutherland Quarterly (or treat a friend) and we’ll send you the Sutherland House book of your choice at no charge. To pre-order a single copy, go here.

Launched in 2022, Sutherland Quarterly is an exciting new series of captivating essays on current affairs by some of Canada’s finest writers, published individually as books and also available by annual subscription—four great books a year, mailed to your door, for just $67.99. Subscribe now at sutherlandquarterly.com and we’ll immediately be in touch to send you the free book of your choice.

Thanks for reading. Please either:

Our Newsletter Roll (suggestions welcome)

Kwame Fraser’s Kwame Eff, “economic democracy, political economy of Canadian arts and culture, etc.”

Banuta Rubess’s Funny, You Don’t Look Bookish, reviews five books a week.

The Bibliophile from Biblioasis, an independent publisher based in Windsor.

The Literary Review of Canada’s Bookworm, “your weekly dose of exclusive reviews, book excerpts, and more.”

Art Kavanagh’s Talk about books: Book discussion and criticism.

Gayla Gray’s SoNovelicious: Books, reading, writing, and bookstores.

Esoterica Magazine: Literature and popular culture.

Benjamin Errett’s Get Wit Quick, literature and other fun stuff

Lydia Perovic’s Long Play: literature and music.

Tim Carmody’s Amazon Chronicles: an eye on the monster.

Jason Logan’s Urban Color Report: adventures in ink (sign-up at bottom of page)

Anne Trubek’s Notes from a Small Press: like SHuSH, but different

Art Canada Institute: a reliable source of Canadian arts info/opinion

Kate McKean’s Agents & Books: an interesting angle on the literary world

Rebecca Eckler’s Re:Book: unpretentious recommendations

Anna Sproul Latimer’s How to Glow in the Dark: interesting advice

John Biggs Great Reads: strong recommendations

Steven Beattie’s That Shakespearean Rag, a newsy blog about books and reading

Mark Dykeman’s How About This: Atlantic Canadian interviews and thoughts on writing and creativity.

J. W. Ellenhall’s 3-Page Book Battles: Readers help her choose which of three random books to review each month.

Donald Brackett’s Embodied Meanings: “Arts music films literature and popular culture.”

I have a very nostalgic feeling about this whole era because my mom went to the UK around this time on a business trip. I was a bookworm of a child and had long lists of books unavailable in India that I wanted her to get for me. She happened upon a wonderful bookseller in a store in London who recommended some real bangers to her, including the first Harry Potter and great intro Discworld books (Men at Arms, Guards, Guards and Equal Rites). In total, she brought back 32 books, a whole suitcase-worth.

She was understandably a little peeved when I read the first Harry Potter and then immediately asked why she hadn’t immediately bought the second too. If recall, that was a period when the second book had just come out but the series wasn’t quite as red-hot as it eventually became but super buzzy.

I was fascinated by the differing accounts of how the first Harry Potter book came to be accepted by Bloomsbury. What stood out for me was Cunningham's statement: "I think it was because I didn't come from a traditional background. I'd come from marketing and promotion. I'd seen how children relate to books, so I perhaps wasn't looking for those kinds of books that tried to teach them lessons, or tried to be good for them." A remarkably high proportion of books published for kids today still try teach them moralistic lessons of a very particular sort. By contrast, what distinguishes the Harry Potter books is strong old-fashioned story-telling, a fascinating range of characters, and highly imaginative world-building. Dickens would have approved.