This is the 290th edition of SHuSH, the newsletter of The Sutherland House Inc. If you’re new here, press the button:

Sutherland House is always happy to receive submissions of manuscripts or proposals for nonfiction books. If you are looking to get published, contact submissions@sutherlandhousebooks.com. No agent required.

If you haven’t had a chance to read the comments from last week’s SHuSH, “Mark Carney’s next book,” please do. A lot of interesting perspectives on the publishing habits of our leaders and betters. I particularly appreciate Howard White’s contribution of the term “maplewashing.”

This is chapter three of our look at Bloomsbury Publishing, the most successful new book publishing venture in the last half century. I’ve left part one, SHuSH 286, “The Bloomsbury Miracle,” and part two, SHuSH 287, “An Exceedingly Fortuitous Moment,” outside the paywall for those of you who aren’t caught up.

We last looked in on the four original partners of Bloomsbury in summer 1986. They had just orchestrated simultaneous resignations from their previous jobs. They had raised £2 million, leased offices above a Chinese restaurant in Putney, and started hiring thirty more employees and commissioning the hundred books they hoped to publish in year one.

Asked how it would distinguish itself from the publishing herd, CEO Nigel Newton said Bloomsbury’s mission was “to be a publisher of works of excellence and originality.” He still uses that line, as though every other publisher aims for mediocre and derivative.

A more honest answer would have started with Bloomsbury’s deep pockets and its willingness to pay handsomely for the best books available—distinctive features for a new player. Beyond that, the company consistently pursued books combining high quality and commercial potential, which not all publishers target, or consistently find.

Newton likes to boast that in its first year or two, Bloomsbury signed Mary Flanagan, Jeanette Winterson, Margaret Atwood, Joanna Trollope, Brian Moore, Jay McInerney, Nadine Gordimer, John Irving, and Michael Ondaatje. There is definite excellence on that list, although not an abundance of originality. Editor Liz Calder poached Gordimer, Irving, and Atwood from her former employer. Each of the authors mentioned by Newton was either established or had published an impressive debut before working with Bloomsbury, and in most cases the company was acquiring rights to North American works rather than originating projects. There were also straight commercial releases on the list, such as a book of Marilyn Monroe photos.

The commercial titles were necessary because Bloomsbury had put itself in a bit of a bind. As a new company, it had no deep backlist of previously published material to sustain it in difficult times. It was almost entirely dependent on the current year’s releases to keep its head above water. So it was paying huge advances for high-potential books, including £340,000 pounds for an authorized biography of Samuel Beckett, and £400,000 pounds for the world rights to David Mason’s Little Brother, and hoping that sufficient sales would materialize to cover those bets and pay the bills. Every publishing season was a role of the dice.

It was nevertheless an impressive start from a publishing perspective. Many bestsellers, many awards. In its early years, Bloomsbury gained a reputation for throwing good parties, Bollinger on tap, and for hosting sales conferences in such locales as Berlin, Versailles, and Venice. It told writers that it was putting 5 per cent of the equity of the company into something called the Bloomsbury Author’s Trust. This promised to create a windfall for its authors when the company went public five or ten years down the line.

By 1994, as Bloomsbury prepared to list on the London Stock Exchange, it had about £8.5 million in sales and an operating margin of £850,000. Expectation was that its market capitalization would be around £8-10 million, or slightly more than one-times-revenue, meaning investors didn’t see it as a particularly attractive stock.

The listing raised about £3 million in new capital for Bloomsbury, which it used to start a children’s imprint, a line of reference books, and a paperback division—all standard moves in the publisher playbook of the era. Authors who signed with the company in its first five years received about £300,000, hardly a windfall. It amounted to an average of £600 per book (roughly $1,000) if they’d been hitting their target of 100 books a year, and it was doled out on the basis of sales, so the largest cheques likely went to the authors who’d had the largest advances. Still, a nice thing to do.

Over the next several years, the company sold more books. Its revenues climbed to about £14 million by 1997 and its profits inched up to around £1.4 million. That’s solid performance—it’s not easy to grow a profitable business at any time. Newton and gang had successfully created a mid-sized independent house.

But Bloomsbury had launched on investor capital and from the perspective of its funders, the results had to be disappointing. Stock markets were booming in the mid-nineties. Bloomsbury’s initial June 1994 share price of .41 cents had sunk to .26 cents by January 1998. It wasn’t much to show for all that talent, all that money, all those books and big-time authors.

I wonder how things looked to the founders at this time. They had to be pleased that they were getting good books and growing revenues, but the enterprise had been predicated on the notion that it could earn a good return on investors’ cash. There are huge advantages to launching a business with other people’s money, until the other people start wondering what they’re getting out of it.

The founders also had a stake in Bloomsbury’s share price, although a small one. As far as I can tell, Newton, CEO and chairman, has never owned more than 4 per cent of Bloomsbury’s stock. I expect he was feeling exposed around this time. The company, as an investment vehicle, was stalled, and outside shareholders controlled his fate.

I think about that 4 per cent. Newton made Bloomsbury happen. He has been its unquestioned leader since inception. No one has put more on the line than him. And he’s never owned more than 4 per cent of the company. He’s been as much an employee of Bloomsbury as an owner/founder. All that initial capital allowed the company to start big, but Newton and his launch partners gave up almost all the equity in Bloomsbury to gain it—an enormous price.

So that’s where things were by 1997, the end of Bloomsbury’s first decade. In some ways a success, in other ways not. Neither a desperate situation, nor an easy one.

It’s impossible to say what would have happened had Bloomsbury not been hit by lightning in the last months of 1997. Almost literally.

The following synopsis went on display in the British Library in 2017 and, as everyone knows, the scar it mentions was lightning shaped:

Support Independent Publishing

Sutherland Quarterly recently released Laurent Carbonneau’s At The Trough: The Rise and Rise of Canada’s Corporate Welfare Bums. You can read an excerpt, “Corporate Welfare is Canada’s Most Expensive Addiction,” here in The Walrus.

As a SHuSH reader, you are eligible for this special offer: buy a subscription to Sutherland Quarterly (or treat a friend) and we’ll send you the Sutherland House book of your choice at no charge.

Launched in 2022, Sutherland Quarterly is an exciting new series of captivating essays on current affairs by some of Canada’s finest writers, published individually as books and also available by annual subscription—four great books a year, mailed to your door, for just $67.99. Subscribe now at sutherlandquarterly.com and we’ll immediately be in touch to send you the free book of your choice.

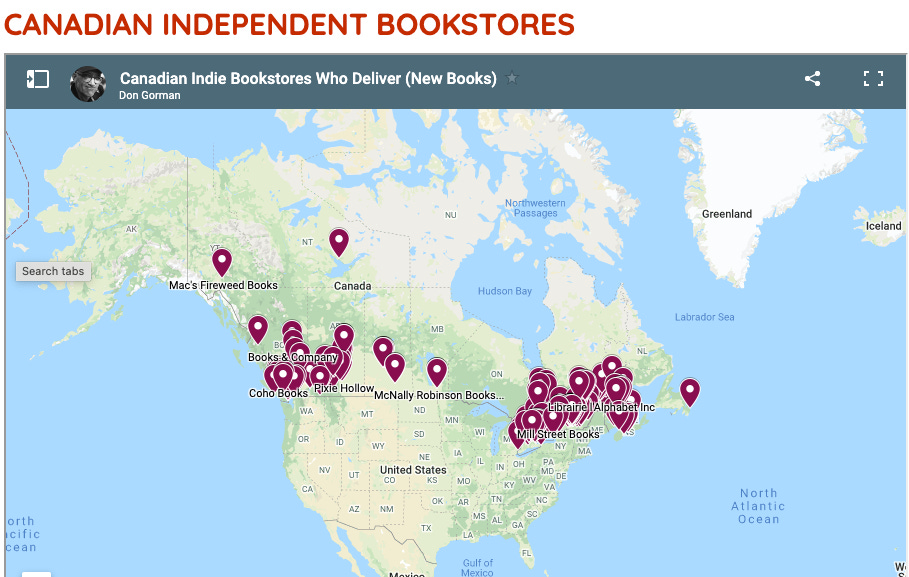

Our regular reminder to readers to support independent booksellers. Click this link for a full list of Canadian stores.

Our Books Newsletter Roll (suggestions welcome)

Kwame Fraser’s Kwame Eff, “economic democracy, political economy of Canadian arts and culture, etc.”

Banuta Rubess’s Funny, You Don’t Look Bookish, reviews five books a week.

The Bibliophile from Biblioasis, an independent publisher based in Windsor.

The Literary Review of Canada’s Bookworm, “your weekly dose of exclusive reviews, book excerpts, and more.”

Art Kavanagh’s Talk about books: Book discussion and criticism.

Gayla Gray’s SoNovelicious: Books, reading, writing, and bookstores.

Esoterica Magazine: Literature and popular culture.

Benjamin Errett’s Get Wit Quick, literature and other fun stuff

Lydia Perovic’s Long Play: literature and music.

Tim Carmody’s Amazon Chronicles: an eye on the monster.

Jason Logan’s Urban Color Report: adventures in ink (sign-up at bottom of page)

Anne Trubek’s Notes from a Small Press: like SHuSH, but different

Art Canada Institute: a reliable source of Canadian arts info/opinion

Kate McKean’s Agents & Books: an interesting angle on the literary world

Rebecca Eckler’s Re:Book: unpretentious recommendations

Anna Sproul Latimer’s How to Glow in the Dark: interesting advice

John Biggs Great Reads: strong recommendations

Steven Beattie’s That Shakespearean Rag, a newsy blog about books and reading

Mark Dykeman’s How About This: Atlantic Canadian interviews and thoughts on writing and creativity.

J. W. Ellenhall’s 3-Page Book Battles: Readers help her choose which of three random books to review each month.

Donald Brackett’s Embodied Meanings: “Arts music films literature and popular culture.”

Thanks for reading. Please either:

Such an interesting account of Bloomsbury's rise - with the lightening bolt at the end! And such an expertly written synopsis of the first Harry Potter book, which we're given a taste of. An interesting synopsis must be the most difficult thing for a writer to produce. This one demonstrates J.K. Rowling's remarkable talent. You can't help but want to read the book.