This is the 291st edition of SHuSH, the newsletter of The Sutherland House Inc. If you’re new here, press the button:

Sutherland House is always happy to receive submissions of manuscripts or proposals for nonfiction books. If you are looking to get published, contact submissions@sutherlandhousebooks.com. No agent required.

Some of you have asked what happened to Timo, the intern we hired a couple of months ago and stuck for most of a week in a storage locker unpacking, separating, organizing, and repacking the 5,500 books that came our way from the Fitzhenry & Whiteside group. He can’t possibly still be around, can he? What miserable task did you assign him to next?

We’ll let him provide his own update:

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

On June 27, The Walrus, one of Canada’s few magazines that pays attention to books, published “Small Press, Big Machines, and the Last Run of Canada’s Most Stubborn Publisher,” by novelist Thea Lim.

I had problems with the headline. The list of contestants for the title of Canada’s Most Stubborn Publisher is as long as my arm, and I’d put money on Coach House’s Stan Bevington or Harbour’s Howie White or Lorimer’s Jim Lorimer, all of whom have put in fifty-plus years, ahead of Gaspereau’s Andrew Steeves, the subject of Lim’s story.

Gaspereau was established in Nova Scotia’s Annapolis Valley in 1997. “By the end of 2025,” writes Lim, the “green Gaspereau building, its tremendous machines, its shelves loaded with slabs of overrun book jackets waiting for reprints, will be gone.” You need to be stubborn to last twenty-eight years, but on the scale of Canadian independent publishing stubbornness, that leaves you middle of the pack.

Pretty much everyone I’ve spoken to in the independent publishing world is upset about the article. The consensus seems to be that Lim and The Walrus did something of a hatchet job on Steeves.

That’s not how it hit me.

I read Lim describing how Steeves and his partner, Gary Dunfield, built a unique operation where everything happened under their roof: “acquisitions, editorial, publicity, sales, shipping, distribution, and IT. But more famously, they do all design, typesetting, printing, and binding on site.” Somehow they managed to make it work while avoiding Amazon, publishing mostly poetry and short stories (as opposed to better selling fiction and nonfiction), and doing commercial printing jobs on the side to help cover costs.

I learned that it meant a lot to Steeves to make books by hand to the highest levels of craftsmanship, that Gaspereau’s beautiful books have won all kinds of design awards, as well as their share of literary awards, and that some of their releases are treasured “like the rare pressings of an iconic record label.”

I read that Steeves is deeply rooted in Nova Scotia and sees himself as part of a local community. He wears his politics on his sleeve and won’t abandon his principles to make a buck. He believes the art Gaspereau puts into a book is as important as what the author brings to it.

In short, Steeves is a crank, in the best sense of the word: opinionated, unorthodox, obsessive. He’s interested in what he’s interested in, he lives the way he wants to live, works the way he wants to work, and doesn’t apologize for it. Lim quotes many people, not least the writers Gaspereau published, who appreciate him for that.

She goes on to say Steeves has “a cultural cunning that’s thrilling,” that he might be a genius—a visionary a la Jeff Koons—and that he might have pulled off a “miracle.” She says he looks like Matt Damon.

She can take that hatchet to me anytime.

Yet I can see how someone who knows, likes, and admires Steeves would take exception to parts of the story (Dunfield apparently didn’t speak and is largely absent from it). Lim puts a higher value on the author’s contribution to a book and is occasionally dismissive of the printing arts. She quotes people saying that Gaspereau can’t be bothered to properly edit and publicize what it publishes. She’s a bit rude to Nova Scotia.

Lim doesn’t like that Steeves hesitated before ultimately making a suddenly-in-demand, prize-winning book available to the mass market because it couldn’t be done by the usual Gaspereau methods. (There’s a lot of he-said, she-said, and hurt feelings on this point and I can’t be bothered. The book was made available, nobody died.)

It annoys Lim that Steeves is prone to grand political statements, but doesn’t feel as strongly as she does about the need for diversity on a publishing list, or the Giller Prize having had a sponsor invested in an Israeli arms manufacturer. (This dimension of the article gave me flashbacks to the New Star affair—old-left publisher closes doors amid a clash with progressive imperatives.) They’re entitled to their opinions.

Lim admits to an agenda in her article. She set out to learn if Gaspereau might serve as a higher-minded alternative to an increasingly commercial, consolidated, and algorithmic publishing sector.

She concludes that Gaspereau wasn’t that.

And it wasn’t.

Nor, from what I’ve read, was it intended to be. I don’t know Steeves or Dunfield (or Lim), but they seem to have been more interested in opting out of the publishing industry than posing as an example to it.

So I question Lim’s premise, and I think her timing was suboptimal. She basically showed up at the Gaspereau wake and shouted ‘you’re not all that.’ I mean, I’ve done worse. Journalists are supposed to ask tough questions, speak hard truths, step on toes. It doesn’t always go over well. Sometimes you pay for it, and sometimes you deserve it.

Here’s two things I think were quite valuable in her article.

I spent a good piece of this week talking with journalists about how old media is collapsing and new media is struggling to be born. We ended up in a fight. Some wanted the big guys to hurry up and die to clear the field; others still eke out livings with the big guys and look to them to uphold fading standards. Some thought the new guys are close to breaking through and that a lack of confidence in their future reflects a loser mentality; others thought this delusional and that the upstarts will inevitably be crushed by some combination of Google, Meta, and AI. It ended in a chorus of fuck-yous, a reflection, I think, of the fact that livelihoods are on the line, and that everyone toiling in the cultural space these days is anxious and exhausted.

Lim vs Steeves is a similar (albeit more civil) conversation about the same critical issues. Everyone’s trying to figure out how to make it work amid the cultural industry’s deteriorating economics, how to hold on to standards and values on platforms that have none, and a whole lot else. It is anxious-making. It is exhausting. Lim doesn’t ever land exactly what exploded the Steeves-Dunfield partnership at Gaspereau, but it did blow up and Steeves is clearly distressed by it. Lim herself is feeling bleak and depressed about her lot as an author. The business is hard, whichever direction you look. The article captures that in multiple dimensions.

Secondly, Lim gave readers more than her own take. A magazine editor knows that assigning talented free-thinking journalists to stories is a crapshoot. You send them out and you can never be certain what they’ll come back with. End of the day, you may not like what they have to say. I expect that Walrus editor Carmine Starnino, who has published five books with Gaspereau, was hoping Lim delivered something a notch more celebratory than this piece. But all the complimentary stuff I mentioned above is right there. In abundance. Sometimes over the top … Matt Damon?

Lim rendered Steeves complicated, charismatic, imperfect. She is clear where she stands—Gaspereau’s not the answer she’s looking for—and she lets Steeves be clear where he stands. She gives readers enough to make up their own minds. I wouldn’t want to publish the way Steeves publishes—I barely have the patience to run a photocopier, let alone a Heidelberg Kord 64—and I don’t always agree with his worldview, but I read the article and found myself cheering his audacity, independence, irascibility, and accomplishments. He’s as imperfect as the rest of us, and there’s still much to admire.

Good work all around.

Thanks for reading. Please either:

Support Independent Publishing

Sutherland Quarterly recently released Laurent Carbonneau’s At The Trough: The Rise and Rise of Canada’s Corporate Welfare Bums. You can read an excerpt, “Corporate Welfare is Canada’s Most Expensive Addiction,” here in The Walrus.

As a SHuSH reader, you are eligible for this special offer: buy a subscription to Sutherland Quarterly (or treat a friend) and we’ll send you the Sutherland House book of your choice at no charge.

Launched in 2022, Sutherland Quarterly is an exciting new series of captivating essays on current affairs by some of Canada’s finest writers, published individually as books and also available by annual subscription—four great books a year, mailed to your door, for just $67.99. Subscribe now at sutherlandquarterly.com and we’ll immediately be in touch to send you the free book of your choice.

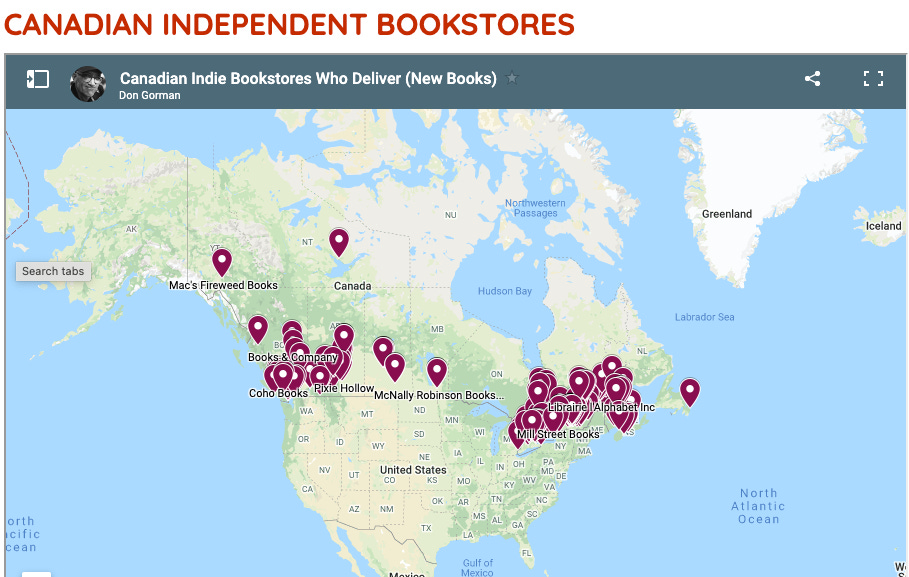

Our regular reminder to readers to support independent booksellers. Click this link for a full list of Canadian stores.

Our Books Newsletter Roll (suggestions welcome)

Kwame Fraser’s Kwame Eff, “economic democracy, political economy of Canadian arts and culture, etc.”

Banuta Rubess’s Funny, You Don’t Look Bookish, reviews five books a week.

The Bibliophile from Biblioasis, an independent publisher based in Windsor.

The Literary Review of Canada’s Bookworm, “your weekly dose of exclusive reviews, book excerpts, and more.”

Art Kavanagh’s Talk about books: Book discussion and criticism.

Gayla Gray’s SoNovelicious: Books, reading, writing, and bookstores.

Esoterica Magazine: Literature and popular culture.

Benjamin Errett’s Get Wit Quick, literature and other fun stuff

Lydia Perovic’s Long Play: literature and music.

Tim Carmody’s Amazon Chronicles: an eye on the monster.

Jason Logan’s Urban Color Report: adventures in ink (sign-up at bottom of page)

Anne Trubek’s Notes from a Small Press: like SHuSH, but different

Art Canada Institute: a reliable source of Canadian arts info/opinion

Kate McKean’s Agents & Books: an interesting angle on the literary world

Rebecca Eckler’s Re:Book: unpretentious recommendations

Anna Sproul Latimer’s How to Glow in the Dark: interesting advice

John Biggs Great Reads: strong recommendations

Steven Beattie’s That Shakespearean Rag, a newsy blog about books and reading

Mark Dykeman’s How About This: Atlantic Canadian interviews and thoughts on writing and creativity.

J. W. Ellenhall’s 3-Page Book Battles: Readers help her choose which of three random books to review each month.

Donald Brackett’s Embodied Meanings: “Arts music films literature and popular culture.”

I like that Timo's name is Timon The Painter-of-Icons. (it's an Orthodox Christian thingy)