Last Post?

This is the 313th edition of SHuSH, the newsletter of The Sutherland House Inc. If you’re new here, press the button—it’s free:

Sutherland House is always happy to receive submissions of manuscripts or proposals for nonfiction books. If you are looking to get published, contact submissions@sutherlandhousebooks.com. Agents welcome, but no agent required.

At some point in the early 1980s, I was assigned to write a magazine article on the death of the drive-in movie theatre. The occasion was the closure of two drive-ins in Edmonton, victims of suburban sprawl and rising land values.

As usual, I started my reporting at the library, digging into a now forgotten reference annual called the Canadian Periodical Index (a catalogue of every magazine story written in the country organized by subject). I went back, year after year, to find stories on the business of drive-in movies, reading them on microfiche. When I got to around 1957, I found an article by the great Peter C. Newman, then a cub reporter at the Financial Post, declaring the death of the drive-in. His peg had been the closure of some theatres in the Toronto area. He blamed land values and the onslaught of television. He’d beaten me to the story by twenty-five years.

I also checked a US periodical reference and read up on the history of the drive-in, which dated to 1921. Some now forgotten entrepreneur in Comanche, Texas, exhibited silent movies to car-bound patrons in a cow pasture. The practice spread, aided by a total absence of drunk-driving legislation.

Drive-ins were indeed dying by the 1980s, even before everyone had a home video machine and a Blockbuster card. The survivors relied on a heavy diet of horror films, much like movie theatres today. The trend was so obvious it was caricatured. Joe Bob Briggs was just starting to make a name for himself as the world’s only drive-in movie critic.

Joe Bob was the creation of John Bloom, a Vanderbilt-educated cinema critic for the Dallas Times Herald. Bloom had been under pressure from his bosses to devote more attention and enthusiasm to movies people actually watched, rather than critical darlings. So he adopted the persona of Joe Bob, who patronized drive-ins in his maroon 1972 Olds Toronado with curb feelers, accompanied by his girlfriend, Wanda Bodine of La Bodine hair salon. Joe Bob met drive-in fare at its own level. His rating system counted naked boobs and buckets of blood. I was the first person outside of Texas to interview Bloom about his character, who went on to become nationally syndicated and land a TV show. He was a very pleasant man.

Anyway, where was I?

Oh, yes, The Washington Post.

The Washington Post dumped a third of its workforce this week. Vanity Fair reported that “hundreds of staffers would be laid off, nearly a third of the roughly 800-person newsroom. The Post shut down its sports desk and books section, gutted its international team, and drastically reduced local coverage.”

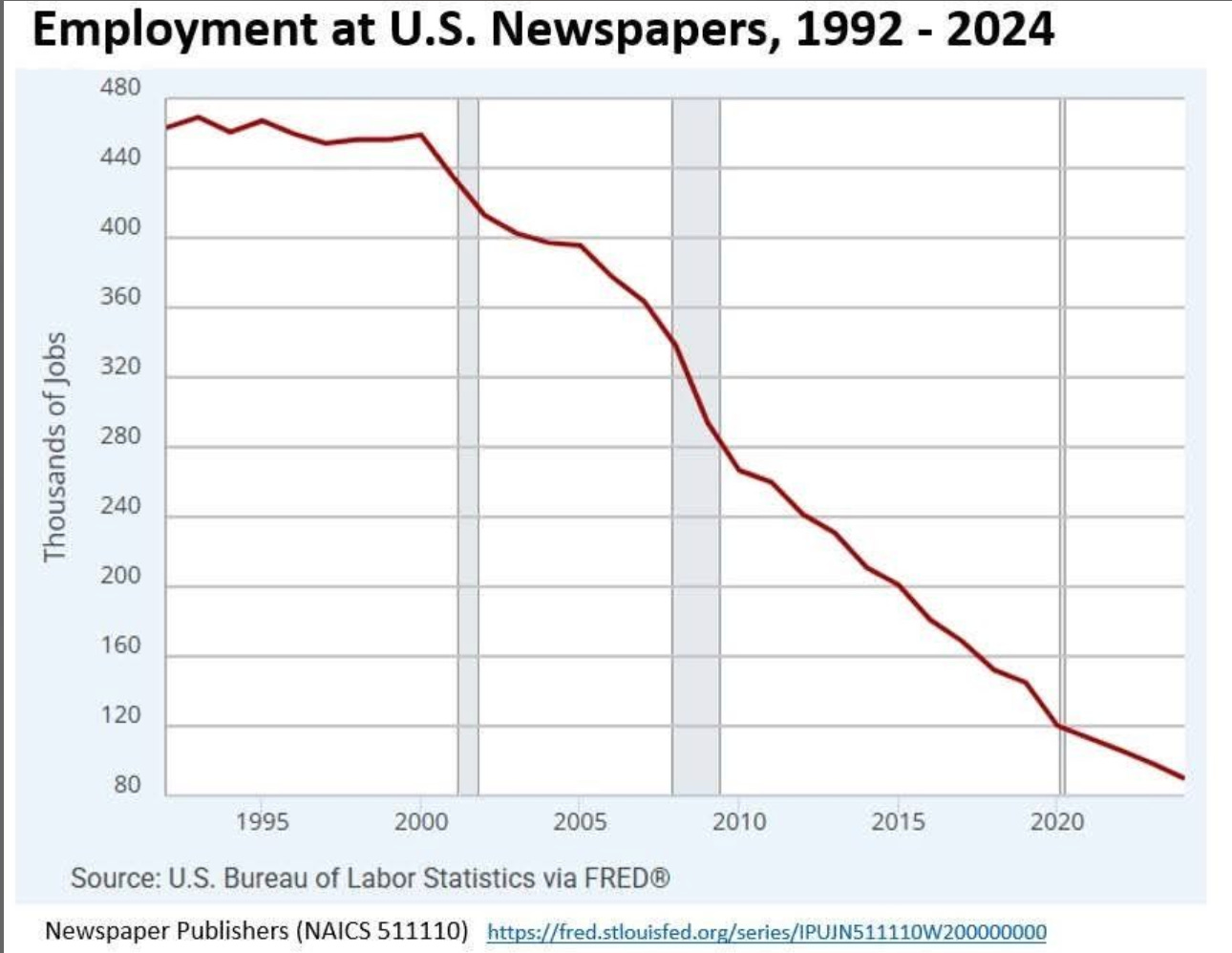

The layoffs are being interpreted as a betrayal of the newspaper by its owner, Amazon-founder Jeff Bezos. He’s said to be currying favour with Trump by destroying a newspaper that should be holding him to account. That’s not altogether wrong. Bezos’s administration-friendly policies have cost the Post a big chunk of its audience and exacerbated its losses. But it’s mostly wrong. What happened to the Washington Post is what’s happened to every other newspaper in North America. The business model was killed by the internet. Bezos, who bought the paper off a scrap heap in 2013, used his deep pockets to keep it in a state of unreality until this week, when the Post finally began chasing its peers:

It is nevertheless a tragedy, and Bezos did break his promises to the paper and its readers. He deserves infamy. Many more great journalists are now out of work and one of the last American bastions of book criticism has fallen. If forced to choose, I might have taken the Post’s book coverage over that of the New York Times. It wasn’t quite as comprehensive, but neither was it as hidebound and suffocatingly New York. I followed the bylines of Ron Charles and Michael Dirda religiously. Both are now gone.

Charles is taking it good-naturedly: “How a major national newspaper will carry on without someone on staff to summarize the plots of midlist literary novels is beyond me.” He has already washed up here on Substack. Dirda writes books and contributes to the TLS and the New York Review of Books, so I doubt we’ve heard the last of him, either.

The Post’s news has triggered another round of commentary on the death of newspapers and the decline of literary review culture.

I’ve been reading stories about the death of the newspaper for more than twenty years. Philip Meyer wrote The Vanishing Newspaper in 2005, predicting that the last print copy would be discarded by the last newspaper reader in 2043. When I got deep into newspaper history for my Hearst book, I learned there were prophets of newspaper doom in the early years of the twentieth century when a shift in the business model from subscriber revenue to advertising revenue prompted a wave of consolidation. There were subsequent rounds of doomsaying with the advent of radio and television.

The first article I can recall reading on the decline of book reviewing was Elizabeth Hardwick’s The Decline of Book Reviewing, published in Harper’s in 1959 and discovered by me about a quarter-century later. Her point was that reviews were becoming lazy, bland, dishonest, promotional, and harder to find in newspapers and magazines. She wanted searching, authoritative criticism that treated books as central to cultural life. I subsequently learned that people had been lamenting the decline of reviewing for almost as long as reviews have existed. Samuel Johnson thought all reviewers were hacks. More recently, complaints about the quality of reviews has been almost entirely overtaken by astonishment at their near total disappearance.

We need to reconcile ourselves to the fact that both newspapers and the practice of book reviewing are no longer central to our culture—they are indeed on extinction watch. When I say “we,” I mean me. I feel the decline of newspapers and review culture as loss. I take it personally when newspapers and their book sections are diminished. I think it’s sad that there are so few outlets you can turn to for rigorous, authoritative discussion of books or anything else happening in the world.

The sadness is to an extent misplaced. There were real problems with a media space dominated by a relatively small number of outlets whose employees enjoyed outsized influence on the shape of public conversation (of course, it was great if you worked at one and were doing the shaping). There were similar problems with the old book review culture. It was an insular, top-down conversation. Only certain people were chosen to review books. Only certain books were selected to be reviewed. The fractured media landscape we have today is relatively undisciplined and chaotic, but it is far more democratic, and in some ways more meritocratic than what came before. Certain things have been lost, others gained—it’s just different and, for most participants, less remunerative.

My younger colleagues have never read newspapers and never will. The notion of a book review culture, which in my head is a whole ecosystem of norms, practices, and institutions through which books are evaluated and offered for public consideration, does not obtain for them. If I was in my twenties, I doubt I’d care much about the fate of my grandfather’s Washington Post. I’d be revelling in the reams of great writing on this platform, following any number of online literary sites (LitHub and The Millions and digital quarterlies and micro-publications), listening to some of the many book-oriented podcasts, and sharing pieces on social because they’re compelling, regardless of provenance. I’d be looking more to individual voices and communities of like-minded readers than to institutions. I’d be fine. There’s still a big conversation about books raging out there, so long as you’re not just looking for it in all the old places and expecting it to follow the old rules.

But I still find the Washington Post news sad. There’s no substitute for a team of informed people trained to write intelligently and interestingly for a broad audience—professionals whose work is well edited and well presented. My culture feels diminished as a result of this news.

It was by way of coping that I recalled the drive-in story. It’s not that drive-ins matter much. They don’t. They just remind me that cultural obituaries are almost always premature. I was still going to drive-ins every summer well into the streaming era, in fact, right up to the pandemic. There’s one or two remaining in most major cities, sixty years after Peter C. Newman wrote them off. There are still a few serious print outlets devoted to reviewing books, and there are still 500 journalists employed at the Washington Post. They’ll likely be around for years to come. We need to enjoy them while they still exist, buying ourselves time to adapt to change and appreciate the new.

We don’t know what’s coming. My death of the drive-in story landed amid a spate of stories about the death of Hollywood. The auteur revolution of the seventies—Coppola, Scorsese, Altman, etc.—was spent. Jerry Bruckheimer blockbusters were viewed as the end of serious filmmaking. Home video was going to put the cinema out of business. It wouldn’t be long, we read, before there was nothing worth watching. Hollywood was indeed in slow decline, and it’s not looking any better today, but there’s now more to watch than ever.

We’re quick with obituaries for cultural things. Often what’s needed is a forwarding address.

Start the year informed

As a SHuSH subscriber, you are eligible for this special offer: buy a subscription to Sutherland Quarterly (or treat a friend) and we’ll send you the Sutherland House book of your choice at no charge.

Launched in 2022, Sutherland Quarterly is an exciting new series of captivating essays on current affairs by some of Canada’s finest writers, published individually as books and also available by annual subscription—four great books a year, mailed to your door, for just $67.99. Subscribe now at sutherlandquarterly.com and we’ll immediately be in touch to send you the free book of your choice.

Sutherland Quarterly is also pleased to announce its next edition, coming January 27, will be Richard Stursberg’s Lament for a Literature, a sweeping account of how English Canada once forged a confident literary culture—and how that culture has steadily collapsed.

For decades, books provided the country’s most searching reflections on its history, politics, and identity; they shaped the national conversation and anchored a shared sense of who Canadians were. Author and media executive Richard Stursberg traces how this ecosystem emerged, flourished, and then eroded. He follows the rise of a vigorous publishing industry in the 1960s and ’70s, the period when Canadian writers reached international prominence, and the subsequent decades in which foreign ownership, shifting cultural priorities, fragile institutions, and policy failures hollowed out the sector.

Clear, forceful, and grounded in deep research, Lament for a Literature shows what happens when a nation loses the infrastructure that sustains its stories—and outlines practical reforms, including a Canadian Book Law, to rebuild the foundations of a literary culture capable of renewing itself.

Thanks for reading. Please either:

Our Newsletter Roll (suggestions welcome)

Banuta Rubess’s Funny, You Don’t Look Bookish, reviews five books a week.

The Bibliophile from Biblioasis, an independent publisher based in Windsor.

The Literary Review of Canada’s Bookworm, “your weekly dose of exclusive reviews, book excerpts, and more.”

Art Kavanagh’s Talk about books: Book discussion and criticism.

Gayla Gray’s SoNovelicious: Books, reading, writing, and bookstores.

Esoterica Magazine: Literature and popular culture.

Benjamin Errett’s Get Wit Quick, literature and other fun stuff

Lydia Perovic’s Long Play: literature and music.

Jason Logan’s Urban Color Report: adventures in ink (sign-up at bottom of page)

Anne Trubek’s Notes from a Small Press: like SHuSH, but different

Art Canada Institute: a reliable source of Canadian arts info/opinion

Kate McKean’s Agents & Books: an interesting angle on the literary world

Rebecca Eckler’s Re:Book: unpretentious recommendations

Anna Sproul Latimer’s How to Glow in the Dark: interesting advice

John Biggs Great Reads: strong recommendations

Steven Beattie’s That Shakespearean Rag, a newsy blog about books and reading

Mark Dykeman’s How About This: Atlantic Canadian interviews and thoughts on writing and creativity.

J. W. Ellenhall’s 3-Page Book Battles: Readers help her choose which of three random books to review each month.

Donald Brackett’s Embodied Meanings: “Arts music films literature and popular culture.”

I so enjoyed the reviews of the nonfiction book critic Becca Rothfeld. Such a shame.

This is one of the best things I've read on the Post situation, and probably the only piece that made me laugh. Cultural obituaries are almost always premature, and the impulse says more about the declarer's nostalgia than the thing itself.

But I want to resist any consolation, or at least complicate it, because some deaths really are deaths. Like you said, a team of editors and reporters at an institution with resources, standards, and a mandate to cover the world is different thing than a gifted individual writing from their kitchen.

That's not coming back in a new shape. It's a loss. The meritocratic framing of the new landscape is true but also it's a story we tell ourselves to avoid grieving what we've actually lost.

I loved this piece. I just don't want to let us off the hook.