This is the 283rd edition of SHuSH, the newsletter of The Sutherland House Inc. If you’re new here, press the button:

Sutherland House is always happy to receive submissions of manuscripts or proposals for nonfiction books. If you are looking to get published, contact submissions@sutherlandhousebooks.com. No agent required.

I managed to give myself a headache last night reading a big bunch of articles about why men don’t read fiction. If you search hard enough, you’ll find everything bad in the world—MAGA, gun violence, human trafficking, the Filet-o-Fish—attributed to the reluctance of males to engage with novels.

An essay by David Morris in the New York Times six months ago, “The Disappearance of Literary Men Should Worry Everyone,” seems to have prompted this round of handwringing. The American Spectator torqued it up to “The War on White Male Fiction Writers,” and the flood of takes and counter-takes shows no sign of abating.

An absence of reliable research on the subject accounts, in part, for all the noise. Fears and projections fill the void, and we’re left trying to decipher passages like this from Vox author Constance Grady:

2024 was in many ways the year of what writer Max Read calls the Zynternet, as in dudes who chew a lot of Zyn nicotine pouches: “a broad community of fratty, horndog, boorishly provocative 20- and sometimes (embarrassingly) 30-somethings—mostly but by no means entirely male.” It’s arguably the community that most of the “why did men pick Trump” postmortems are talking about, and what [is referred to in] laments that too many young men are turning to figures like Joe Rogan and Andrew Tate for intellectual stimulation.

The Zynternet bro is the most visible male archetype of the year, the first to present itself to our collective cultural imagination when we think “man.” And no, he does not read.

Notwithstanding that passage, I’m grateful to Constance Grady for painstakingly surveying the available data and coming tentatively, sensibly, to a supportable conclusion: “Do American men read less fiction than women do? Probably. Do they read so little fiction that women buy 80 percent of all the units in the marketplace? Maybe. It doesn’t look like anyone has actually fact-checked this question in quite a while.”

You can see here some of the challenges involved in measuring reading habits. Are we talking reading books or purchasing books? Does buying correlate to reading or are women better gift givers? What about those hugely popular 20-part, 60-page-per-instalment romance series that might ratchet up purchases by women—anything like that in the fiction market for men? Should we base assumptions about readership of literary fiction on data about readership of general fiction, as many of the articles I’ve read do?

All we can safely say is that it does seem men read somewhat less fiction than women; they also read fewer books of any kind. As a person in the book industry, I wish that weren’t so, but it may not be a cultural calamity.

The most interesting article I came across in last night’s binge was published in 2009 by the University of Saskatchewan’s Virginia Wilson in Evidence Based Library and Information Practice. She undertook a small study of boys aged four through twelve, interviewing them about their reading habits. Her theoretical perspective was that if anyone was ever going to understand the reading habits of boys, they needed to recognize that the experts were the boys themselves. She quizzed forty-three of them about their book collections, what they liked and didn’t like, and their motives for reading.

Each of the boys had a personal collection of books. These ranged from eight to 398 volumes, with a median of 98. All but one of the boys had fiction in his collection. The most prominent genres were fantasy, science fiction, sports stories, and humour. The boys had no time for love stories, books about groups of girls, and such classic children’s fiction as The Adventures of Robin Hood.

Asked about their favourite books, most of the boys pointed to a non-fiction title: joke books, magic books, sports books, survival guides, science books, references, atlases, dinosaur books.

The boys also read a good deal of non-book material: comics, manga, magazines, sticker books, puzzle books, and catalogues. A number mentioned reading video game manuals, both to learn more about the games, but also to heighten their enjoyment of the narratives within the games.

The manuals were part of a bent toward pragmatic reading, something they found useful as much as pleasurable. The boys often read to support another hobby—Pokémon, for instance. They also appreciated non-linear texts and plenty of illustrations.

Interestingly, many of the boys tended to discount their own reading. They often described the informational stuff they liked—those video game manuals or computer guides or research materials for science projects—as “not really being reading.” Serious reading, in their minds, involved novels and conventional non-fiction books.

Wilson’s conclusion was that at least part of the “boys and reading problem” might come down to what counts as reading. Informational nonfiction, comic books, computer magazines, graphic novels, and role-playing game manuals were “not necessarily privileged by libraries, schools, or even by the boys themselves.”

Of course, as Wilson notes, one shouldn’t generalize too much from a small qualitative study involving forty-three boys. There’s nothing definitive to be learned here about Trump or contemporary masculinity (although I’ve read several lengthy screeds based on less).

Wilson’s paper simply reminds us that reading is complicated, and most of the available research on reading habits isn’t. Survey respondents are typically asked if they read books for leisure, or if they’ve read a book in the last year. There are many reasons to read other than for leisure. There are many things to read other than books. And not all books are equal.

I haven’t seen a study that tracks if men spend more minutes per day reading sentences than women. Or one that drills down to find who reads the most newspapers, magazines, websites, newsletters, contracts, annual reports, research papers, instruction manuals, catalogues, and cereal boxes. Each of those formats is as potentially edifying (if not as much fun) as Morning Glory Milking Farm: A Monster Bait Romance, with its 47,570 enthusiastic ratings on Goodreads.

I read so many concerns for and condemnations of contemporary males last night that it came as a surprise to learn that our most reliable measure of reading competence, the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies, finds no real difference in literacy of men and women aged 16 to 64 in the US or Canada. We should all revisit that baseline before assigning responsibility for the state of civilization to whoever is or isn’t reading or buying contemporary fiction. (PIAAC did find that while Canadian literacy scores have been stable, US scores have slipped 5 percent since Trump was first elected. Make of that what you will.)

Does the men-and-fiction problem exist? I think yes, and my sense is that it’s one of both supply (what’s getting published) and demand (what men will read). I thought I’d have more than that to say. This is my kind of issue—the whole point of SHuSH is ill-considered opinion drawn from shaky evidence on a weekly timetable—but I can’t compete with what I’m reading, so I’m backing off for now.

In the meantime, two braver souls, Sutherland House author Lydia Perovic and novelist Russell Smith, will try to sort things out this month at Society Clubhouse in Toronto. It looks like fun:

Support independent publishing!

As a SHuSH reader, you are eligible for this special offer: buy a subscription to Sutherland Quarterly (or treat a friend) and we’ll send you the Sutherland House book of your choice at no charge.

Launched in 2022, Sutherland Quarterly is an exciting new series of captivating essays on current affairs by some of Canada’s finest writers, published individually as books and also available by annual subscription—four great books a year, mailed to your door, for just $67.99. Subscribe now at sutherlandquarterly.com and we’ll immediately be in touch to send you the free book of your choice.

Sutherland Quarterly is also pleased to announce its newest edition is Laurent Carbonneau’s At The Trough: The Rise and Rise of Canada’s Corporate Welfare Bums.

From the railroad excesses of the nineteenth century to the Trudeau government’s record-breaking payouts to profitable multi-nationals such as Volkswagen and Stellantis, journalist and policy analyst Laurent Carbonneau demonstrates how Canadian governments of all stripes repeatedly prioritize short-term politics and corporate lobbying over long-term public welfare.

Year after year, federal and provincial politicians write huge cheques to private enterprise in the name of industrial strategy. Year after year, these generous grants and tax breaks enrich corporate shareholders (often foreign) while doing next to nothing to enhance economic development. It is an appalling misuse of public money at a time when Canadians, who pay for this largesse through their taxes, are grappling with unaffordable housing, over-stretched healthcare and childcare services, and stagnating wages.

With humour and shrewd analysis, Carbonneau issues a timely call to action, urging Canadians to demand a fairer, more prosperous economy designed for the public good, not corporate interests.

A searing critique of Canada’s long-standing reliance on corporate subsidies.

Laurent Carbonneau is a policy professional working primarily on innovation, science and technology issues, with previous experience on Parliament Hill and national campaigns working for the NDP Leader's Office and a senior member of caucus.

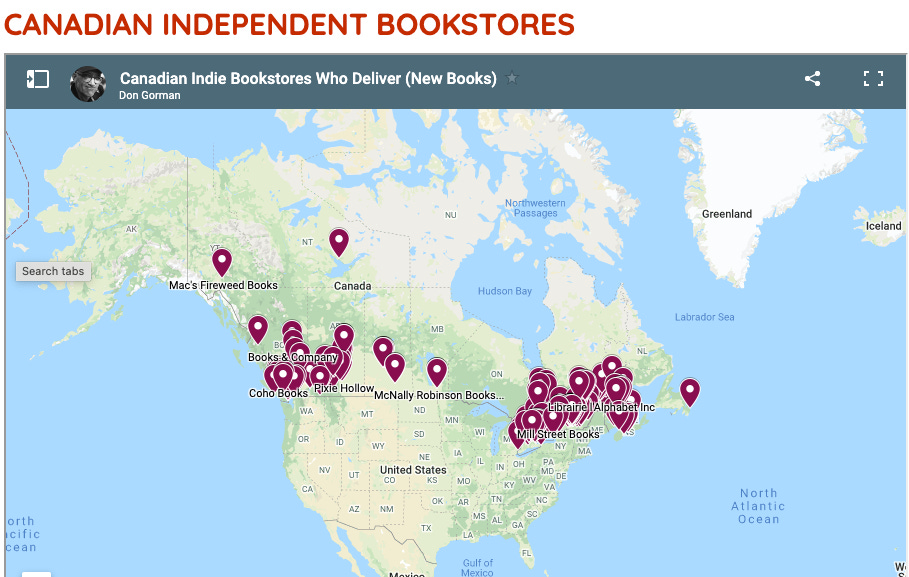

Our regular reminder to readers to support independent booksellers. Click this link to make the above map come alive.

Our Newsletter Roll (suggestions welcome)

Kwame Fraser’s Kwame Eff, “economic democracy, political economy of Canadian arts and culture, etc.”

Banuta Rubess’s Funny, You Don’t Look Bookish, reviews five books a week.

The Bibliophile from Biblioasis, an independent publisher based in Windsor.

The Literary Review of Canada’s Bookworm, “your weekly dose of exclusive reviews, book excerpts, and more.”

Art Kavanagh’s Talk about books: Book discussion and criticism.

Gayla Gray’s SoNovelicious: Books, reading, writing, and bookstores.

Esoterica Magazine: Literature and popular culture.

Benjamin Errett’s Get Wit Quick, literature and other fun stuff

Lydia Perovic’s Long Play: literature and music.

Tim Carmody’s Amazon Chronicles: an eye on the monster.

Jason Logan’s Urban Color Report: adventures in ink (sign-up at bottom of page)

Anne Trubek’s Notes from a Small Press: like SHuSH, but different

Art Canada Institute: a reliable source of Canadian arts info/opinion

Kate McKean’s Agents & Books: an interesting angle on the literary world

Rebecca Eckler’s Re:Book: unpretentious recommendations

Anna Sproul Latimer’s How to Glow in the Dark: interesting advice

John Biggs Great Reads: strong recommendations

Steven Beattie’s That Shakespearean Rag, a newsy blog about books and reading

Mark Dykeman’s How About This: Atlantic Canadian interviews and thoughts on writing and creativity.

J. W. Ellenhall’s 3-Page Book Battles: Readers help her choose which of three random books to review each month.

Donald Brackett’s Embodied Meanings: “Arts music films literature and popular culture.”

Thanks for reading. Please either:

When was the last time you saw a movie or TV show with man or boy with a book, where the man/boy was not portrayed as a dork or a psycho?

I have no data or insights about this, but I can share my male friends' reading habits:

Retired engineer, 81 - doesn't read books

Tech businessman, 52 - been reading one long novel (Michener) for the last year

Retired fireman, 65 - only reads news on his phone

Optometrist, 61 - occasionally reads graphic or YA novels

College librarian, 64 - regular reader but only NF (history, politics)

Retired banker, 77 - reads a couple of spy novels a year

Retired lawyer, 73 - regular reads a variety of non-fiction

And finally, my golfing buddy, a retired English literature professor, age 72, who has not read a book in the last five years. Pretty dismal showing, for a sample of older, university-educated men.